Fridae.com readers will remember the controversy that erupted in Hong Kong in June 2008 when Hong Kong film maker Danny Cheng Wan Cheung, better known by his nickname Scud (which he chose, he says, to match his Chinese name, which translates as 'Scudding Clouds'), brought out his first feature film, City Without Baseball. Scud found himself assailed from all sides, from the conservative for using a real group of Hong Kong baseball players to make a very sexy and homoerotic movie with a gay character, and by tongzhi groups for defending one of those baseball stars who made homophobic remarks on Hong Kong's Radio 2. Scud is as fiercely protective of his cast and crew as he is of showing reality as he sees it.

To him that reality includes letting people say what they think, even if you don't like what they say. I think he enjoyed the argument he caused; he's that kind of guy, as you could have told from his choice of movie; who else would have focused on baseball in this city? So it's not surprising that he's done it again with his most recent film, Permanent Residence, both writing and directing a meditation on two subjects still pretty much avoided here, death and the love of two men, one gay, one straight. Scud just isn't interested in fitting into any neat category.

For such a small and rather sweet looking guy, and for all his apparent reticence, he's got a ruggedness of character the unwary had better look out for. He knows exactly what he thinks and will tell you about it if you push him. Maybe it was his upbringing in China, or maybe it was the way he's had to battle through 22 years of work in software commerce before getting to make films. After getting his degree in applied computing from Hong Kong's Open University, Scud went to Australia in 2001, returning three years later to found his film production company, Artwalker, and to make City Without Baseball. Up till then he'd hung around with a lot of film people, saw what they'd done and learned from them, so when he started Artwalker he had no qualms about jumping right in.

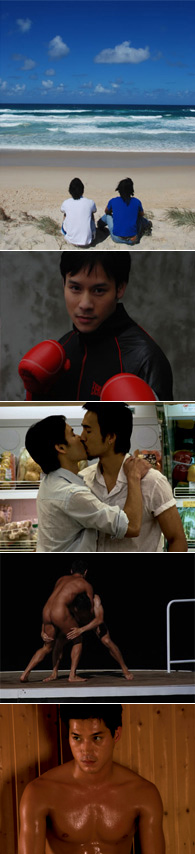

We meet in Artwalker's studio and offices in a surprisingly smart building in Causeway Bay, where the cast and crew of Permanent Residence are back to BBQ together to celebrate the completion of the film and its opening in Hong Kong on Apr 23. I am ushered into a quiet part of the studio to preview the movie then and there. Afterwards, I talk to its director and his leading man, Sean Li, over a late night glass of wine. I confess to being staggered by the movie, by what is at times its visual beauty (the cinematography excels), by the sheer unlikelihood of its themes and by the acting, which is good enough to persuade you to accept the reality of the tortured love affair at the heart of it all.

But why the focus on death? From the film's opening the signs and reminders of mortality multiply at every hand, from the death of key figures in the plot to seemingly minor details like coffin-shaped drawers under the bed. Nightmares stalk its characters. Death's darkness pervades the love affair of the two men; it is provocative, disturbing.

"I try in my films to make things as difficult as possible," Scud answers, "to show the reality of love in whatever form it takes. I want to show the influence death has on our lives, not just at their end. The most difficult question of all is death." He makes it clear to me that he doesn't care for long life as such. "I wanted to show that death, as inevitable, is something to be prepared for and met with a mind at peace after completing all the expectations we set ourselves in life," he adds.

He makes one of his characters reflect on dying by thirty; this is a personal reflection. Amazingly at the age of 43, Scud believes he himself is almost at the point where he has so little time left that he is in something of a rush to complete his life's work. I confess to being taken aback by this; he is adamant that it is true. Showing this in his film wasn't difficult, since most of the things that he wrote into it had occurred to him personally, so much so that the only difficulty he faced was to choose what to include.

"The film is not as sad as I could have made it," he expands on this point, "and this is not a film about a fairy tale." Much of what happens to Ivan, Sean Li's character and the film's gay protagonist, and to Windson, the straight lover played by Osman Hung, Scud says, is taken from his own life story, so he puts his own words into the mouths of his characters, one of whom says "We can be dead, but not weak or old." Does Scud believe this? Possibly, but then maybe not; Windson's Chinese name, incorporating sea and mountain, also seems to mean eternal life. There are hints in the film that Scud hopes we can extend our existence after death, maybe meet again in whatever hell we are destined for.

The on-the-face-of-it unlikely love affair between gay Ivan and straight Windson turns out, too, to be almost entirely autobiographical, even down to its smaller details. Ivan is an IT executive, as, of course, was Scud. Ivan gains fame in later life as a film maker, whose first acclaimed work is about baseball. Ditto Scud. If it were not for these corroborating pieces of evidence, a good many of us would doubt the premise of the film, that a straight man can be in love over so many years with a gay guy and still refuse to have sex with him, can, indeed, go to the length at one point of characterising his friend as his wife whilst denying that he is the love of his partner's life. Scud portrays almost without comment the layers of denial that it is possible to live under to be able to sustain such a viewpoint. Windson and Ivan are inseparable for years. Windson's family accept Ivan; he is the 'bonus son', a better son, in fact, than his lover. They sleep together, lie on each other's body, but they never make love. Only once does Windson almost permit himself to cross this last physical barrier; at night, in a dark corner on a stairway by the beach, the pair come close. Windson's arm at last begins to fold around Ivan's back, only for a passer by to interrupt them and they flee into the night. This is the only moment of true physical intimacy between the two.

"Is this a set up, a tease?" I ask Scud. "No, not at all, it's real, just as it happened," he replies. "we even shot the scene in the exact spot it happened to me." Ivan's frustrated lust is painful, to him and to the audience, which is with him when he can stand it no longer and jerks off by their shared bed alongside Windson's sleeping form.

At times, this is an intensely erotic film. Though this may sound really surprising in a film where the love affair, one that lasts for many years, remains unrequited, in effect the delay and frustration serve to enhance the desire. Bodies, incredible looking bodies in full nudity, arouse the eye throughout. Both the two lovers are boxers and martial artists and possess bodies sculpted to match. The camera lingers on the muscles, shadows and light play on the lust. The movie deliberately sets out to attract and to shock. In a Hong Kong supermarket Ivan kisses the man who had awakened his homosexual self-awareness, sending housewives and their shopping trolleys scurrying. Wrestling together on the beach, sunbathing on a diving raft, the lovers are both classic statements of male beauty. Fetish and fantasy flow from fixation and frustration; Ivan sees himself stripped and abused in a Thai go-go boy joint. Soft porn? Perhaps, but the blade of the audience's desire has to be whetted if it is to feel Ivan's dilemma, his never ending frustrated desire.

Sean Li, who, as most of Hong Kong's gay community will be devastated to learn, is straight (as is the entire cast), was born in Hong Kong but raised and educated in England. He took a degree in engineering at Bath University then got a job with a company which seconded him to Hong Kong, where he modelled for a while. By chance he was overheard in conversation by Scud, who was sitting at the next table in a restaurant in Tai Hang.

Scud, then making City Without Baseball, saw immediately that Sean fitted the image of what he was seeking for his second film, hired him on the spot and sent him off to prepare for it at the New York Lee Strasberg Theatre and Film Institute. By chance, Sean had already acted in a short film there named Have a Ball while on holiday a few years before. He's totally cool about playing a gay man, and about spending so much time on screen in the nude. It's the professional approach he learned with his method acting at the same New York theatre school that fostered the likes of Al Pacino and Sean Penn.

I asked him whether he thought that playing a gay lover called for different approach. "Yes, I am sure so. You talk about different things with a guy, have more in common, share more with another man than you might with a woman. Maybe you can go further with a man in that way," he muses. But he doesn't see this film as just a gay film, rather a love story of a different kind.

And it will not be his last with Scud, who looks set to carry on this exploration his life in further films. He plans a trilogy, centred on his life and the concept of limitation; Permanent Residence is about the limit of life; his next film, Amphetamine, already made, is about the limits of passion. Last will come Life of an Artist, a film about the limits of art. But other films seem to get in the way of what Scud considers his lifetime's major work; Permanent Residence should have come first, but somehow City Without Baseball caught his attention and muscled in. So we may perhaps expect a few more films along the way.

So back to the title, Permanent Residence, which I can see by now refers both to our permanent residence in the many mansions of our existence and to our home in the heart. Whatever our fate, to whichever hell we descend after we die, we may live on, Scud seems to say, in the final goal we have striven for.

Why did Scud make this film, one so harrowingly autobiographical? "This is the life of quite a few people", he replies. "A straight man can love a gay man and not have sex, or maybe he can have sex. What matters most to me is love, not its physical climax. Love is the toughest part." And what matters is making a film that is true to the life he sees in front of his camera lens. A film that is true to his life.

Permanent Residence is showing at Broadway Circuit Cinemas (Palace IFC and Cinematique) from April 23. The official website with trailer is at permanent-residence.com The official Permanent Residence:The Album book is available online on Fridae Shop.