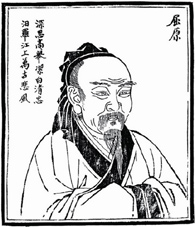

A growing chorus of voices is challenging the official narrative of the great Warring States poet Qu Yuan (屈原) as a patriot who, in an apparent suicide in 278 BC, threw himself into the Miluo River holding a heavy rock to protest against the alliance of the state of Chu with the hegemonic Qin state.

The poet's memory is honoured annually today on Duanwu Festival (端午节) by millions of ethnic Chinese around the world with the eating of rice dumplings, which according to legend, were thrown off dragon boats by locals to feed the fish so they would not feed on his corpse.

Academics have proferred another reason for Qu Yuan's suicide than his supposed love for the nation. The poet, they say, was more of a romantic than a patriot, and it was his love for -- and subsequent abandonment -- by the King Huai of Chu (楚怀王) that led him to immerse himself into the river.

The thesis that Qu Yuan was a homosexual and a lover of his king was first put forth in 1944 by the Sichuan scholar Sun Cizhou. In Li Sao 《离骚》 ("Departing in Sorrow"), an allegorical poem in the Chuci 《楚辞》 poetry anthology, Qu Yuan falls into depression after his rejection by his lord and slanderous attacks by jealous officials surrounding the king.

Qu Yuan's references to the king as "美人" (beautiful man, or beautiful person) and "灵修" (restoration of the soul) were both terms widely used by women at that time to characterise their lovers, according to Sun. The poet's eventual suicide because the king had found other new lovers was a love story, not a patriotic story, said Sun.

Sun's views, while widely controversial at the time, came to be accepted by other notable academics. The Chuci expert Wen Yiduo (闻一多), for instance, described Sun's thesis as "completely correct.”

“Sun’s idea that Qu Yuan was a ‘弄臣’ [Editor's note: someone who offers entertainment to kings or emperors] is completely correct and grounded on historical facts...To be frank, Qu Yuan’s significance in literature will not only be diminished but might be enhanced. I believe we literature critics would welcome the facts Sun has presented, and not reject them.” wrote Wen at the time.

Chi Zhen (池桢), a history researcher at Tianjin-based Nankai University, later noted that Qu Yuan in fact had the ambition to improve his country's politics through his relationship with the king.

“‘美政’ (beautiful politics) was Qu Yuan’s ultimate ideal. It was the politics based on his pure and everlasting love with King Huai of Chu. In this relationship, both people have a shared and noble political ideal and, pushed by love, both strive for the well-being of the country and people,” wrote Chi in an essay published in 2007.

The poet's memory is honoured annually today (Jun 12) on

Duanwu Festival (端午节) by millions of ethnic Chinese around the world

with the eating of rice dumplings, which according to legend,

were thrown off dragon boats by locals to feed the fish

so they would not feed on his corpse.

Such an idea was once close to reality when Qu Yuan was, at the height of his career, loved by King Huai of Chu. However, as the king gradually deserted him and the power struggle worsened, Qu’s dream soon shattered, and his “ Utopia based on homosexual politics disappeared in the Miluo River.”

Fang Gang (方刚), associate professor of gender studies at Beijing Forestry University, believes that Duanwu Festival is the first gay Valentine's Day in the history of civilisation, and that the recognisation of it as such would be a big move in "rectifying the name" (正名) of both Qu Yuan and the origins of the festival.

Sociologist Liu Chongshun (刘崇顺), however, remains cynical that Fang’s attempts to reposition the festival will be fruitful.

"The image of Qu Yuan (as a patriot) is one that has been formed over two millenia, and has become an immovable fixture in the history, culture and psyche of China," wrote Liu. "Inasmuch as Fang Gang's assertions may be grounded in reality, this is not something that can be changed overnight by anyone."

The debate over whether Duanwu Festival can rightly be called a gay Valentine's Day has ignited rancorous debate on microblogging platforms in China.

”This is an utter humiliation to years of traditional Chinese culture," fumed one Sina Weibo user.

"Even if Qu Yuan was really gay, must we remember him based on his sexual orientation?" asked another.

“This makes me want to throw up!" wrote yet another. "Why should society celebrate a phenomenon so perverse and evil as homosexuality?"

The criticisms, however, have not dampened the enthusiasm of members of China's LGBT community in claiming Duanwu Festival as their own Valentine's Day.

A-qiang, a Guangdong-based gay activist, wished his followers a “Happy Gay Valentine’s Day!” on the morning of the festival, and others have been following suit.

Amidst the debate, a voice of reason was offered by Zhu Xueqin, a feminist and psychiatrist based in Shanghai.

"Some gay people in China have completely embraced gay festivals from abroad -- Pride, and Stonewall and what have you. They're ready to accept history as told to them by others because it has nothing to do with China," she observed. "Whether Qu Yuan is gay or not is unimportant. The question here is why heterosexuals can have any day they want as Valentine's -- 2/14, 11/11, 5/20, 7/7 -- but when gay people want just one day, they're expected to provide a historical basis?"

"Why is it when people are told Qu Yuan committed suicide for the love of the nation, they are able to accept it without questioning, but when they're told Qu Yuan committed suicide because of love (for another man), they demand that you show proof and evidence? Why is there this double standard?"

This article is republished with permission from shanghaiist.com.