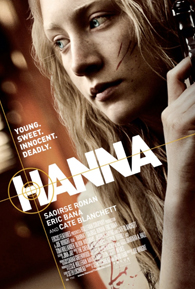

Hanna is one of the more satisfying action films to come out in a year that has been relatively dry of them. The story is tight, the direction is uncommonly tough and riveting, the fight choreography is slick, the cinematography is clear and striking, and the score by the electronic group The Chemical Brothers is both sinister and whimsical.

All of which is well and good, because it did irritate this reviewer to discover how admittedly predictable Hanna is. No one who has been paying attention to action films of the past 20 years will really find the story all that surprising. Consider the setup: the titular character (Saoirse Ronan) is a girl 16 years young, bred from birth to be a formidable killing machine somewhere in northern Finland by her father (Eric Bana). They await the day when she will be good enough to take on her enemies, who want her and her father dead at all costs. Raised without music, art or any real friends, she longs deep in her heart for the beauty of those things.

The day arrives when her enemies show up. Their leader is the devious CIA operative Marissa Weigler (Cate Blanchett) and soon both daddy and Hanna are on the run from Weigler and her eccentric henchman, Isaacs (Tom Hollander), a campy, gay but no less deadly German assassin and torturer. On the way, Hanna falls in with a nice hippie family who are cruising around Morocco and Spain in their recreational vehicle, and their daughter takes a shine to her very odd new friend.

Anyone intimately familiar with the various tropes of action movies of the past 20 years should have no problem in seeing where this setup leads, pretty much aided by how the film drops numerous fairy tale type clues and symbolism throughout that should be pretty blatant to anyone who spent any time with Andersen and Grimm.

At its best, however Hanna feels like a much needed update to the action films of Luc Besson at his peak in the mid-90s: The Professional, Danny the Dog (written by, but not directed by Besson) and even The Fifth Element. From Jean Reno’s stone cold professional assassin to Jet Li’s illiterate cagefighter to Milla Jovovich’s childlike demigoddess, Besson’s protagonists in those films were apparently soulless, violent individuals who were redeemed by the unselfish love and friendship of another human being. Saoirse Ronan proves more than equal to this task, aided by Seth Lochhead’s and David Farr’s script, which is superior to most entries in this genre.

Fast becoming one of today’s most unpredictable and challenging young actresses, Ronan is not one to shy from difficult parts such as the spirit of a raped and murdered girl in The Lovely Bones. Her Hanna is equally deadly, awkward, and possessed of a pure, animalistic innocence, much like the wolf cubs she strokes lovingly early on in the film, and no more a killer than a wolf cub is. The supporting players are pretty competent too. Particularly outstanding are Jessica Barden as the chatty, boy-crazy daughter of the family Hanna falls in with, and Olivia Williams as the goofy, wise hippy matriarch. The weak link is strangely Blanchett as the designer-suited, fright-wigged CIA operative Marissa, who despite a strong and very hilarious introduction, is reduced in the end to not much more than a standard-issue wicked stepmother and malicious vamp with designer threads.

Its solid technical credentials and deeper-than-average writing make Hanna a predictable but engaging thriller driven by a solid central performance from Saoirse Ronan. If you know what you’re getting, it’s a good film to get it with.