Oh, East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet,

Till Earth and Sky stand presently at God’s great Judgment Seat

Living for much of his life in the East, Kipling understood half of this equation well, but to him, any judgment involved here would have been simple: one handed down to a largely heathen and barbaric East by the civilising West. Rob McBride is a playwright, who, like Kipling, is also a journalist, though one whose view of the world appears on the TV screen rather than in Kipling’s newsprint, but for him the balance is much more complicated than that. Judgment, in his dark and disturbing new play, Katoey, is dispensed not before the Almighty’s judgment seat but in the dank and fetid police station in Phuket run by the deeply corrupt Lieutenant Somchai of the Thai Tourist Police. Here, East and West come face to face in the person of Sai, a katoey, or ‘ladyboy’, one night ‘lover’ of naïve Australian sex-tourist Jonno, from whose wallet ‘she’ seems to have removed the entire contents whilst her ‘lover’ satisfied sexual urges so obtuse that he failed, in good M Butterfly fashion, to even notice that ‘she’ was as yet still a man.

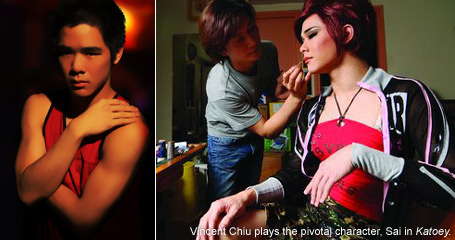

One of the mysteries in this play is that we are for ever unsure whether Sai is really a transgendered she or rather has chosen to act as a ‘she’ for her own reasons; with the possibility of the latter (and ‘she’ definitely has yet to have the operation), I have inserted inverted commas around the pronoun, which I hope will not offend. Sai is the pivotal character in the Not So Loud Theatre Company’s premiere staging of McBride’s play, which ran for its first showing at the Hong Kong Fringe Club between 9 and 13 June this year. This is its second airing in public, as it was featured as a one act drama in El Dorado’s play reading series focussing on Hong Kong’s English writing playwrights back in June 2008. Despite this, the play is not a recent work. Rob wrote it back in 1998, and although he received a good deal of encouragement to stage it (Playbox in Melbourne, for instance, gave it a glowing review) its intrinsic difficulties kept it out of the public eye till last year.

‘The problem was the casting of the katoey, McBride explains. ‘It’s a very difficult role calling for an actor who can play both boy and girl and speak in two completely different ways. We just couldn’t find someone to fit the part.’ Last year, though, McBride met Vincent Chiu, a drama student at the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts, and found that he had at last got a match (check out Chiu’s face on the poster for some clue as to why McBride was immediately convinced!). The play proved a hit with the public, giving McBride the confidence to expand it to two acts and to stage the play for the first time now.

Katoey is directed by Tom Hope, a veteran Hong Kong director who founded the Not So Loud Theatre Company in 1991 whilst working as a lawyer in Hong Kong. Tom retired from the law in 2003 to take up the theatre as a full time career, returning to England to work at the Old Vic and to stage two productions in London, The Mouse Queen and Slippery Mountain, a Chinese opera which was featured in the ‘China Now’ festival in 2008. His wife is Hong Kong Chinese and Hope has now relocated back to Hong Kong, where he intends to produce and direct plays which will cross pollinate the two cultures in which he lives. Katoey is the first of these, and it is scheduled to re-run later in the year, at that point, he hopes, gaining sufficient funding to be able to cast professional actors. Not that the present strong amateur cast does anything but enhance this play; playwright, director and cast combine here in a performance which provokes thought and troubles conscience.

What had sparked the idea for Katoey back in the early days of McBride’s writing was a conversation in a Hong Kong bar with an Australian acquaintance who had actually fallen prey to exactly the circumstances in which Jonno finds himself. Reporting a theft by what he thought was a female prostitute, he coupled the embarrassment of finding that ‘she’ was a ‘he’ with having to watch the thief being beaten up by the tourist police. There the similarity in the stories ends, though, for McBride’s play delves deep into the characters and twists in ways which would have been closed to his informant and which remain unpredictable to the audience till the end. His play shows the shabby reality that lies beneath the shallow surface scum that is all that is visible to the average Jonno-type tourist.

Of which, of course, there are likely to be a fair few in any audience for this play in the expat East, and the most devious twist of all inflicted upon these by the playwright is that they will find that the facile judgments they might hitherto have expected to make of this tale will be replaced by a need to judge themselves. For this play brings sharply into focus those relationships indulged in by western sex tourists in the poorer countries of Southeast Asia, which, exposed to the harsh lights of the theatre, are not a pretty sight. Sai is a katoey who preys on westerners, maybe what Thais call a katoey thiam, or an ‘artificial katoey’, perhaps (as I have said, it isn’t really clear here) not really male to female transgendered but a boy who lives by the money ‘she’ milks as a woman from the farang (foreign) tourists, dependent, of course, upon those very despised farang to get ‘her’ out of the trap society has caught ‘her’ in. Sai’s life is a vicious chain of corruption and exploitation where the westerner who exploits poor locals for sex is himself exploited for his money, and where pimp and police suck the blood of both.

This perverse ‘industry’, one of Southeast Asia’s greatest growth areas since the American wars of the sixties, hides behind the smiles and glitter of the native cultures, a rotten core in a shiny-skinned fruit. The Dutch scholar Han Ten Brummelhuis has written of this Thai world in Peter Jackson and Gerard Sullivan’s book Lady Boys, Tom Boys, Rent Boys (published by Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books in 2000) , where he describes how the cultural phenomenon of men knowing themselves to be, and often making themselves to be, women, common to countries across the region (the Burmese acault, the Indonesian waria, the Filipino bakla), has been corrupted by western visitors; how the traditional Thai self-labelled ‘second type of woman’ or ‘transformed goddess’ now has to exist alongside the new type of ‘artificial katoey’, who changes gender to catch a westerner to enable ‘her’ to escape ‘her’ economic lot and often ‘her’ country altogether. The ruthless commercial transactions upon which the sex industry is based are made clear elsewhere in the same volume by another Dutchman, Jan Wijngaarden, whose investigation of the lives of Thai bar boys shows how they make a living and, for their families, a whole new way of life, by cleverly manipulating their multiple ‘lovers’. One of these:

“by the age of 19, Thirayut had 23 farang men sending him money, mostly on a monthly basis. He had to write 50 letters a month to keep the contacts going… At one point he had 400,000 baht in his bank account, which he used to build a new concrete house for his parents.”

Personal memoirs tell similar stories. Daniel Gawthorp, a Canadian, spent ten years as a sex tourist in Thailand and elsewhere in Southeast Asia. So smitten was he with the life he led that he took a job with the Thai newspaper The Nation to work in Bangkok for another two. It was then that he realised what had been happening. In his candid memoirs, The Rice Queen Diaries (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2005) he charts the course of his realisation of how he, who has always seen himself as the exploiter, had been exploited:

“For the libertine Rice Queen with missionary tendencies, corruption of the heart goes hand in hand with disillusionment; that stripping away of the glittering illusions that attracted you to Thailand in the first place… those very same farang I now complained about as a resident; the ones who traipse through the Kingdom indulging in their boundless sense of entitlement without even knowing they’re doing it.”

Anyone thinking of emulating Gawthorp would be well advised to see McBride’s play first, which will be possible again here in Hong Kong sometime later in the year, and, both McBride and Hope are hoping, perhaps further afield.