A human smile can you make you feel warm and happy, it may make you laugh, and it certainly goes a long way to making someone feel welcome. Someone’s smile shows their approval. It shows they like you.

It was all of these emotions, all of these these feelings that Eric Hou, a 23-year-old fresh graduate from the northeastern city of Changcun, wanted to give China’s gay community. He wanted to capture smiles from straight people on camera and send them to the Chinese gay world.

“I want to be a bridge between China’s mainstream society and LGBTs,” he said. “Smiles usually represent kind and good intentions. This is something that our gay friends most hope for.”

So on May 20, Hou launched his Smile for Gay project, China’s first national gay outreach campaign. In Chinese, it was called Tongzhi Nihao (同志你好) meaning hello comrade! Comrade is a commonly used term to mean homosexual. With very little resources, he used two popular mainstream websites (Douban.com and Sina.com) and asked straight netizens to upload photos of themselves smiling with a message of encouragement to Chinese gays and lesbians. At the same time he sent bands of volunteers across the country to ask passersby in the street if they’d join. More than 600 volunteers from all corners of the country – including Hong Kong, Yunnan, Inner Mongolia, Sichuan, Guangdong, Beijing, Shanghai and the northeastern region – took to the streets with cameras, whiteboards, badges, leaflets about gay society and of course their own smiles.

The result was amazing.

After a little under two months he collected 4,409 photos.

“In the beginning I was only hoping for 1,000,” he said.

Left to right: "Human rights, freedom to love," "Forget ‘he’ is ‘her’"

and "There’s no rainbow without a storm."

And what a collection it is. Young and old, male and female, people from all walks of life. There are boyfriends and girlfriends, newly-wedded couples and mothers and fathers. One photo shows a middle-aged man in migrant worker clothing. His sign says: “I wish you happiness.”

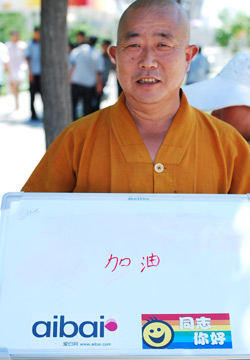

There’s another of a monk, grinning, hold a whiteboard with the words jia you (go for it!).

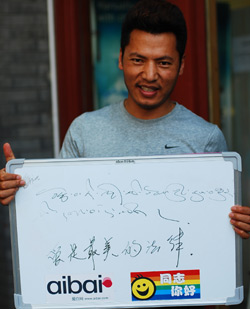

A handsome Tibetan man, who apparently deliberated for 20 minutes before agreeing to take part, holds up his sign with the words in Tibetan script and Chinese saying “Love is the most beautiful law.”

Snapped on her webcam, one girl poses in the nude (modestly cropped), others write words of encouragement on their body. Things got creative.

But perhaps the most arresting of them all was the photo of an old man painting calligraphy with a giant brush near a lake in central Beijing. One of the volunteer teams had asked him if he would take part in their “Tongzhi Nihao” campaign. The old man wasn’t familiar with slang. He thought comrade meant comrade. “Is this something to do with the Red Army?” he asked. After the volunteers explained, he was happy to join the campaign and proceeded to paint the characters jia you tongzhi (Go for it! Gay people!) on the pavement.

Most messages expressed simple support “Our love is the same,” or jia you (go for it!). But there were also more bizarre notes such as: “Go to Denmark and get married,” and “Love is not physics, fixed rules are farts!”

The campaign’s success reflects not only the growing sense of understanding and tolerance towards the gay community in China (largely among the younger generation) but it is also a factor of how the campaign was designed. It’s non-confrontational, the online component is entirely voluntary while on the street volunteers were told to politely back down if passersby were not supportive or expressed homophobic opinions. It’s friendly: who can resist someone asking for your smile? And it’s homegrown: all the volunteers were local Chinese (and according to Hou, about 70% were straight). In this way, it’s much more accommodating to Chinese culture than flamboyant Prides or angry demonstrations could ever be. Beijing police closed down a Mr Gay China beauty pageant in January, while last year Shanghai’s first gay Pride had to cancel some events.

Tongzhi Nihao / Smile for Gay organiser Eric Hou

Hou looks like an unlikely candidate to be an activist, especially in a country like China whose one-party state doesn’t generally tolerate protests. He is short, slight and softly spoken. But at 23, Hou is a veteran activist. When he was just a first-year-student at Chungchun Normal University, four years ago, he founded the Changchun Animal Protection Association. They campaigned against cruelty to pets. Hou organized students to take part in several street protests against the eating of dog and cat meat where they took to the streets waving bloody posters of slaughtered pets and climbed into cages wearing animal masks.

“Five terms can describe who I am,” says Hou. “Buddhist, vegetarian, animal rights, liberalism, and non-violence. My motto: ‘Love and be cool!’”

As the project picked up momentum, it was easier to collect photos, says Hou. Once people could see that so many other people had joined us they were much more willing to also take part. “There weren’t many people that openly and directly opposed us. Those that did were mostly middle- and old-aged,” he adds. One of the more blunt rejections came from a foreigner in Nanning who ripped up the leaflets the Smile for Gay volunteers had given him. He shouted: “It’s not natural.”

Of course, there is still a lot of ignorance and homophobia in China. It wasn’t until 2001 that homosexuality was removed from the list of mental diseases and the older generation still remembers the time when being gay was equated with hooliganism. But increasing positive coverage of gay issues in China is changing opinions says Xian, founder of lesbian help group, Common Language. “It’s a slow steady process, but attitudes to gays have improved a lot especially in the last five years,” she says. “And I think it’s mainly because media is now reporting gay issues, and there are more freedoms on the Internet and these are changing people’s attitudes.”

There was one thing Hou regretted.

“Well, when I got the photo of the Buddhist monk, I tweeted calling for representatives of the other religions – Christianity, Islam – to send in a photo too but we never got any.” There’s still time.

All the photos in this project can be seen on the Tongzhi Nihao / Smile for Gay website. If you are in Beijing, an exhibition of some of the best photos is being exhibited at the Beijing LGBT Centre until 1 September (open weekends to the public).