Three weeks ago, I turned up for a hearing at Singapore’s Court of Appeal. Civil rights lawyer M Ravi was arguing that Singapore’s gay sex law violates our Constitution on grounds of equality.

I was prepared for weary, depressing proceedings. Yet in the words of a fellow gallery sitter, the ensuing scenes were “better than ten episodes of Project Runway.” The judges were openly sympathetic to Ravi’s case, and poured scorn on the Attorney-General Counsel’s counter-arguments. Though it’s usually claimed that the law is unenforced, Justice Judith Prakash received enough evidence to drily state, “It seems that 377A is alive and kicking.”

After court was adjourned, I rushed to work and turned out the following article for Fridae. But I knew another article had to follow: one profiling the unforgettable personalities who’re leading the challenge. The judgement date for the case has not been released.

Naturally, I wanted to talk about the lawyer, M Ravi. He’s gifted with boyish good looks and a natural flamboyance, and well-known for his political activism. He’s challenged the death penalty as a lawyer for Yong Vui Kong, a Malaysian sentenced to death for drug trafficking when he was 19. He’s also stood up for free speech when defending Alan Shadrake, the British writer who condemned Singapore’s legal system in his book Once a Jolly Hangman.

I also wanted to talk about Tan Eng Hong, better known to his friends as Ivan. He was charged with section 377A last year, and he’s consented to allow his case to be the basis of a constitutional challenge to the law. The charge was later dropped and replaced with section 294 for committing an obscene act in public, after Mr Ravi filed the constitutional challenge.

Ivan hasn’t received much attention from even the LGBT media, for several reasons. He’s camera-shy: he’s refused to allow his face to be shown till after the case is closed. He also isn’t what one would call a traditional poster-boy: he’s middle-aged, he’s highly eccentric, and he was arrested because he was having public sex in a toilet. Still, he deserves recognition, because he has had the courage to fight.

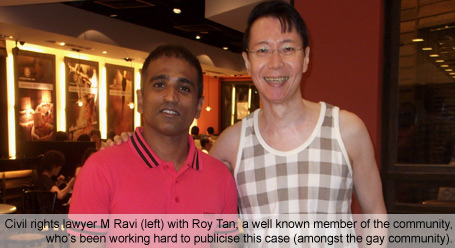

These two figures aren’t the only people working on the case. There’s Indulekshmi Rajeswari, a fresh NUS law graduate and a queer woman, who’s been providing Ravi with legal research, besting even the team of four Deputy Public Prosecutors assembled by the AGC. There’s also Roy Tan, a well known member of the community, who’s been working hard to publicise this case amongst the gay community. (He’s the one in the photos with Ravi – not Ivan!)

However, for the purposes of this article, we’re focusing only on Ravi and Ivan, the lawyer and the defendant. What are their stories? How are they weathering this fight for the gay community?

æ: Age, sex, occupation, location?

Ravi: 42, male, lawyer, Singapore.

Ivan: 48, a male in genetic form, artistic massage therapist, Singapore.

æ: How do you two know each other?

Ravi: I’ve known Ivan for some time because I’m into yoga. I’m a yoga instructor myself, I did the teacher’s training course ten years ago, and Ivan is also involved in holistic stuff.

æ: Ravi, how did you get involved in human rights law?

Ravi: Basically it was because of this Vignes Mourthi case, this death penalty case that was referred to me by prominent opposition leader JB Jeyaratnam in 2003. Basically he felt that important points had not been raised in the Court of Appeal, but [the period for] clemency was over. So it was the eve of the execution and I was trying to convince the Court to give this guy a chance.

After that I felt very unhappy about the way the death penalty has been dealt with in Singapore, and I started this anti-death penalty campaign. And after that I also started to defend [pro-human rights politician] Chee Soon Juan and cross-examine Lee Kuan Yew, defending Falungong and Alan Shadrake recently.

æ: Ivan, what actually happened on the day you got caught?

Ivan: Someone from outside [the toilet cubicle] peeped at my engagement, and they called the police. When we finished and were just about to go out, the police knocked on the door. The police were very intimidating, [they said] “Admit! Admit what were you doing! We have a video taken on the handphone, you’d better admit.” It was time for me to be honest. I didn’t have to continue to tell more stories. We went to Cantonment Police Station, and I had to stay in prison for one day. And of course that it was very painful.

Ravi: So Ivan, basically, when he had this problem, he called me, because he knows that I’m a lawyer. He came to my office downstairs at People’s Park Centre and confessed everything: what happened, and of course that his family knew about it, and he was very embarrassed about it.

æ: Tell us what happened in court.

Ravi: At the first mention, Ivan was basically kneeling down in front of the court saying, “Forgive me, I forgive myself, God forgives me, I forgive the police and everybody.” I was saying to the judge, “This was a very simple application,” and he was doing this!

Ivan: I did say the four healing words of my imperfection, and after that I could be myself and speak. I felt as if a rock was tumbling on my whole life, but being a therapist I knew that I had to celebrate the moment that was prepared for me to face my journey, so I did my best to live my life without fear.

Ravi: We managed to get the case adjourned, and as I came out, Ivan was like, “Oh, you are my saviour, you are my shepherd.”

æ: Did you bring up the constitutionality of 377A at that early stage?

Ravi: At that time I didn’t want to challenge 377A. All I wanted was actually a warning for my client. Ivan’s family was not supportive; his brother and sister were against this, and it was his brother who was bailing him out. But then I realised if we challenged 377A we could reduce the charge. And after some time, even the brother saw the injustice: he said, “Why should he even be charged?”

æ: Ivan, how has the charge affected you so far?

Ivan: It affects my freelance work as a [massage] therapist. I’ve worked at ZoukOut for eight or nine years, but last year it wasn’t me because of the case. I told the organiser I’m caught up in this and I’m troubled by this moment in my life; I had to write in the contract form that I’m involved in this case that and that the date of the court appearance was not settled.

I’m involved in Mission Possible, so I also want to go overseas to help in Japan or with the Chiang Mai missions but I’m afraid my passport will be impounded because of my bankruptcy.

æ: What about the emotional effects?

Ivan: It has not been an easy road. I have all these feelings of entanglement with my family. The house I stay in, my sister’s place, was even painted with some spray paint – and I don’t owe anybody money. But I have had many fellow therapists and good people that surround me, and I hope that the universe will send me the love and energy to pursue this journey. I’ve been listening to these recordings by Belleruth Naparstek about the healing stages of trauma to ease my depression. Plus I’m being counselled by Oogachaga. In fact I have a male and a female counselor that I share my problems with. I have to work out my emotions to learn to accept and let go, and basically forgive. I have learned that the greatest challenge is to be able to forgive every instance of my passage. And of course I have wonderful people around like Roy and Ravi. It was not a coincidence that I knew them. It’s all pre-planned by the universe.

æ: One of the strongest points in your argument is that 377A is still regularly being used. Could you tell us more about this?

Ravi: Just before I filed the application on 24 September, the article came up about two guys in Mustafa Centre. I saw it in Today newspaper: they didn’t have 377A mentioned, but it was very clear what they were charged with because they were given three weeks [in jail]. Look at these two guys. One was a Chinese dishwasher, and the other was a 23-year-old Malay guy. They didn’t have legal representation.

æ: Why didn’t they get representation?

Ravi: There's very little discussion of the sensitivities of GLBT issues in the bar. Tolerance for gay issues is not there. And it’s not like a glorifying case. It’s not like my family is going to be proud, not like with the death penalty.

But as a Hindu, I’m not comfortable with this. Because Hindu philosophy is very simple: we are chanting all the time to God, “You are male, you female, you are either, you are neither.” The figure of Lord Shiva is represented as one third male, one third female and one third neither.

Everything about sexuality is natural as far as Hindu philosophy is concerned.

It is not [just] tolerated, it is natural. So if you don’t accept it, there’s something wrong with your brain. Then you have to go for treatment, and the yogis will smack you.

æ: But of course, the other reason is the class divide. They didn’t have contacts; they didn’t have civil rights lawyer friends like you.

Ravi: Let me tell you, one of the reasons I’m in People’s Park Centre is because there’s access to justice. Sometimes at the kopitiam (local coffeeshop), you see all the people who get charged at the Subordinate Courts. Once I saw a group of transgendered Indians, and basically they were complaining about all the police. They were very unhappy with the fact that the male policemen were handling them roughly. And basically there’s an element of violence there.

And these people are not plugged in to the community as well. They are the marginalised community within the marganisalised community. They are not gay advocacy group People Like Us. They don’t go to Pink Dot. They don’t know everybody who is doing fantastic work in Fridae, or in Sayoni, etc. So when these two guys were charged I said it should end.

æ: You also said 377A is being used in cases other than public sex and non-consensual sex.

Ravi: I was also handling two cases, these two guys, 19, adolescents, Chinese boys. One of them came to me and wanted to do an internship, and he admitted to me he ahs got this problem where he broke up with another guy, and the other guy had gone to the police station to report that they had sex.

This was in 2008 or 2009. And you know what were doing? These [broken-up] guys were counterstriking each other in polytechnic! And all the parents were calling [the police], because they saw it as part of the process of straightening them out. And because it’s a law, the police have to investigate.

This guy… I had to counsel him so much not to commit suicide. And I was doing the death penalty cases at the same time. I don’t have the facilities.

æ: How is your intern now?

Ravi: The boy is fine now, but emotionally very scared. And do you know why? Police criminalisation. His studies: he was an A1 student, but it was all destroyed because of this.

æ: Right now it looks like we’re going to get past the Court of Appeal. What happens after that?

Ravi: This challenge is going to be a long, drawn-out process. I don’t think the High Court will approve. If there’s any hope, it’d be the Court of Appeal [after the High Court ruling].

Whichever way, there’ll be an appeal: if we win at the high court, the prosecution is bound to appeal. So it’s still 50-50.

These are the challenges that are ahead. It’s going to be very interesting. The fight is going to go on and on.