For an introduction, please click here.

Britain's Warwick University's rejection of the Singapore government's invitation to set up a branch campus in the city-state marks the beginning of a new phase of Singapore's liberalisation.

This was the first time that a major foreign investor - the university was expected to invest about £294 million (US$520 million) - turned away because of the state of gay rights in Singapore, among other reasons.

Would they have the freedom to teach and research gay subjects and would a gay and lesbian students' union be tolerated?

These specific concerns did not stand apart from the university's broader concerns about academic freedom, just as gay rights never stand apart from civil rights generally, but what was notable was how, in various statements, public and private, these specific gay-related concerns were raised.

Singapore has been infamous for keeping draconian laws against "gross indecency" between males and "unnatural sex" which includes fellatio and cunnilingus. Additionally, the Singapore government intervenes actively in censoring media that "promote homosexuality."

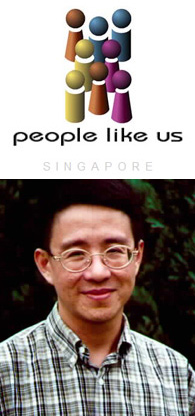

And as is well known internationally by now, the Singapore government has banned the gay advocacy group People Like Us, as well as the Nation and other parties.

Warwick wondered whether such a climate might dissuade high-calibre academics and students who happen to be gay, from their Singapore campus.

Other worries cited by Warwick University's staff and students included the freedom to teach and research certain subjects without falling foul of the government, such as Salman Rushdie's book The Satanic Verses, capital punishment and the political system in Singapore.

The Satanic Verses is among books that are banned in Singapore. Salman Rushdie himself happened to give a talk at Warwick University in the month leading up to the decision regarding the Singapore campus, an event which only reminded Warwick lecturers and students of the bans that Singapore regularly impose on foreign speakers. Discourse against capital punishment is met with great police suspicion and of course, the government is extra-sensitive to any comment about politics locally.

Creeping liberalisation

While it is hard to imagine Singapore changing in ways that might accommodate the gay-related concerns of universities such as Warwick, in fact Singapore has seen creeping liberalisation, and this latest humiliating rejection will quite probably spur some soul-searching. For this reason, the writer thinks it will mark a new phase in Singapore.

In the last five to 10 years, there has been a gradual liberalisation of the arts and entertainment scene in Singapore. Partly, this has been due to homegrown pressure, but also, the government has had an eye to boosting tourism and making Singapore livable for expatriate professionals. For many years, people have complained about how sterile and boring the city was.

After the opening up of China in the late 1980s, much foreign investment headed there rather than to Southeast Asia. This was compounded by the 1997 Asian financial crisis when foreign investment in the region almost dried up completely. Through this period, tourism in Singapore declined steadily.

Spurred into action, the government reexamined why people didn't want to visit or work here, or why Singaporeans remained disgruntled. They began to loosen up a bit to enable a more vibrant arts and entertainment scene. With little fanfare, gay bars, saunas and lesbian nights at various clubs have sprouted. Gay-themed plays, musicals and films have now become almost routine.

But up to a point. Anything that is gay-themed but seeks to change public opinion significantly, or that challenges the definition of morality and the political status quo is still considered suspect. What has been allowed so far fall into three broad categories:

- mass entertainment that has gay characters that are either shallow or stereotypical, thus posing no challenge to homophobic segments of the population;

- niche arts performances that may be more questioning, but which pose no danger to the government's grip on the political agenda because they do not reach a wide audience;

- low-profile social spaces for the gay and lesbian community.

What Warwick University has now done is to suggest that this is not good enough. Learning, enquiry and research cannot be fruitful in such conditions. Nor can they be fruitful if we draw artificial boundaries between education and civic and social life, a point which lay beneath Warwick's questions about whether their publications might be subject to censorship and whether their students could form activist societies.

It probably came as a surprise to the Singapore government how widely Warwick consulted when it did its feasibility study and made its decision.

Warwick engaged Thio Li-Ann, a law academic in the National University of Singapore, to write a report about political and academic freedoms. Thio, in her previous writings, had been fairly critical about Singapore's political system. It should also be noted that she has also been a vocal opponent of equal rights for gays and lesbians, probably on account of her Christian faith.

However, this was balanced by the fact that Warwick also consulted People Like Us (PLU), something that would likely have been a greater surprise to the civil servants charged with netting in a university. Linear thinking - very prevalent in Singapore's civil service - leads to a thought process that often goes like this: PLU has been refused registration under the law, they cannot exist. Therefore they do not exist.

But not only do they exist and are contactable, their opinion may be highly valued by potential foreign investors. In fact, one complaint that the Warwick feasibility study team had was that the civil servants gave them such "by the book" answers when asked about political and academic freedoms, the team was left feeling more uneasy than reassured. All the more, they valued second opinions.

In contrast, PLU could explain clearly how the Singapore system works, and could cite examples of opaque decisions and government clampdowns. Warwick consulted PLU even on matters that went beyond gay-related concerns.

In some ways, PLU advised Warwick, perceptions about Singapore have been more alarmist than real, but in other ways, the government has adopted silly positions that few Singaporeans, no matter how loyal, could defend.

The other notable feature about the Warwick case was how the entire student body and faculty staff got involved in reaching the final decision. The Economic Development Board (EDB), the government arm charged with wooing foreign investment, has hitherto dealt mostly with multinational corporations, whose decisions tend to be based on financial calculations and perhaps political risk, factors which can be called "objective."

Now, given the EDB's mission to make Singapore into a world-class education hub, a new crucial factor has emerged: public perception, perhaps subjective, of authoritarianism in Singapore.

Hitherto, freer arts and entertainment might have been enough to keep corporate executives happy to invest in and relocate to Singapore, but not so when pursuing educational institutions. In order to win their stakeholders over, not only must freedom extend to the intellectual and civic spheres so as to convince feasibility teams, they must also be perceived by foreign constituencies abroad to have been so extended. Any less, and it may prove difficult to realise the dream of attracting cutting-edge teachers, researchers and students.

Kris Olds, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who has studied academic freedom issues in Singapore after teaching for six years at the National University of Singapore told the Financial Times, "The issue [of academic freedom] will need to be grappled with in a systematic way by both local and foreign universities in Singapore and the government over the next one to three years."

Yet education is a major plank of Singapore's economic reengineering. It is not just a question of attracting revenue from students choosing to come to Singapore to study. Top-class educational institutions have a strong multiplier effect, for they are the engines of a knowledge economy that Singapore, a country short on land and natural resources, so clearly needs to be, to survive.

That being the case, Professor Olds is probably right. The Singapore government will grapple with the issue of freedoms somehow. Perhaps very slowly and very reluctantly, but they have no real choice.

Education Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam was quoted by the Straits Times on 22 October 2005 as saying, "Are we at an optimal point now? I doubt it. We must evolve. The intellectual climate is not cast in stone."

He pointedly did not bolt the door.

Alex Au has been a gay activist for over 10 years and is the co-founder of People Like Us. He is also the author of Yawningbread.org where he writes incisively about gay issues, and Singapore life and society.