Several times I have been told that there are no gay Koreans. Fourteen years after Korea's first LGBT organisation was founded, the overwhelming majority of the nation's queers still hide their sexual orientation from family, friends and coworkers. So, unless it's Saturday night in the Seoul districts of Jongno, Sinchon or on Itaewon's "Homo Hill," it's easy to see why many heterosexual Koreans assume the "gay gene" somehow bypassed their peninsula.

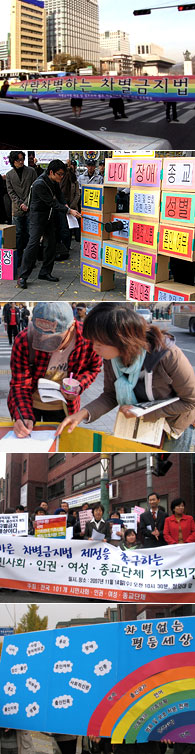

Members of Korea's LGBT community have mobilised themselves to protest the anti-gay Christian fundamentalist lobby's attempt to expressly remove them from the nation's landmark non-discrimination bill. The Bill has since been withdrawn for further study and revision, and is expected to be re-released on Nov 27 before coming to a vote in March 2008. Photos by lgbtact.org

A growing number of foreigners and Koreans alike feel marginalised by how the country's Confucian heritage perpetuates sexist and classist attitudes. In a groundbreaking move intended to encourage social unity, on Oct 2, the South Korean Ministry of Justice (MOJ) announced a bill to criminalise discrimination on 20 grounds, including race, sex, educational status and sexual orientation. Described by the MOJ as "the first fundamental law to actualise the principle of equality, which appears on the Constitution," the law would punish direct and indirect discrimination in the areas of employment, services and education.

But when the draft bill was sent from the MOJ to the Ministry of Government Legislation on its journey toward ratification, seven of the bill's original 20 protections had disappeared. Suddenly, medical history, nationality, language, family type, educational status, criminal or detention record, and sexual orientation were no longer protected classes.

Whereas business interests had advocated for the removal of some groups, it was South Korea's powerful conservative Christian lobby that pressured the Korean Ministry of Justice to exclude civil rights guarantees for sexual minorities.

In October, a group calling itself the Assembly of Scientists Against Embryonic Cloning distributed a petition warning Korean lawmakers that if the non-discrimination bill was passed, "homosexuals will try to seduce everyone, including adolescents; victims will be forced to become homosexuals; and sexual harassment by homosexuals will increase."

According to the group's director, Pusan University Professor Gill Wonpyong, "If homosexuality is allowed, the morals of [Korean] society will immediately collapse and the society will become a world of animals."

Lee Chung Woo, one of Korea's gay rights' pioneers, says that Korean Christian groups are adopting the successful strategies of right-wing religious fanatics in the United States, who exploited widespread ignorance of LGBT issues to achieve their larger political goals.

Unlike some of its Asian neighbours, the South Korean Constitution and Civil Penal Code do not criminalise homosexuality. However, gay men are banned from serving in the military and widespread anti-gay bias in Korean society compels most LGBT Koreans to hide their sexual orientation.

While there have been other issues that mobilised Korea's LGBT community, it was the anti-gay Christian fundamentalist lobby's attempt to expressly remove them from the nation's landmark non-discrimination bill that elicited an unusually potent response. Although South Korea's queer activists are often unwilling to be photographed or filmed, during the protests several of them spoke on camera to national and international media.

In one press release, Han Chae Yoon, the co-chair of the Korean Sexual-Minority Culture and Rights Center (KSCRC) and a Korean LGBT community spokesperson, said: "We are saddened that extremist groups have hijacked this important bill. Lesbian and gay Koreans are your daughters, sons, neighbours and coworkers." Citing the bill's historic nature, she continued, "This law would protect the dignity and human rights that everyone in Korea deserves."

Because South Korea is a signatory of the main United Nations Human Rights Treaties, which are understood to also protect sexual orientation, Han's group worked with New York-based Human Rights Watch. Together, they drafted a letter to South Korea's lawmakers urging them to reinstate civil rights protections for lesbians, gays and bisexuals, as well as to add protections for transgender and transsexual people.

Although quick passage of the bill was originally expected, the ensuing controversy caused it to be withdrawn on Tuesday for further study and revision. It is expected to be re-released on Nov 27 before coming to a vote in the National Assembly sometime in March 2008.

While the fate of the non-discrimination bill remains unclear, the current controversy may have sparked a new era for Korea's iban community. In their zeal to persecute Korea's typically inconspicuous queer population, the right-wing Christian groups may have inadvertently inspired the next generation of Korean LGBT activists.

Sign online petition to protest the removal of the seven categories (including sexual orientation) in the Anti-Discrimination Bill.

Matt Kelley is a gay mixed-race Korean-American living in Seoul. He is currently writing a book about the intersections of race and sex in Korea. His website: www.mattkelley.info.