Several days ago, I was moderating a luncheon talk by Roby Alampay, the Bangkok-based Executive Director of the Southeast Asian Press Alliance. He told a story which typified how Singapore is seen by others.

One day, a friend of his, visiting Singapore for the first time, found herself walking down Orchard Road, the city's main shopping street. It was an ordinary day, with lots of people going about their shopping or socialising. The shop windows were gaily dressed, the crowds in a kaleidoscope of colours. Suddenly, a thought occurred to her and she froze.

It was not that she saw anything untoward. Not at all. The street continued with its buzz. It was just a thought entering her head but it was enough to make her momentarily fearful.

"Oh my God, is it illegal to be dressed entirely in black? Is there a law against it? Am I allowed to be Goth in this city?"

As Roby pointed out, Singapore's reputation as a no-nonsense, big-brother kind of state precedes it. There are plenty of rules, all draconian, and all designed for social control. Media censorship is among the least of them.

Thus, it would not have surprised many Singaporeans that part of Freeheld director Cynthia Wade's Oscar acceptance speech was cut out from the repeat telecast of the Academy Awards (See Fridae's story, 26 Feb 2008). At last year's Oscars, Melissa Etheridge's acceptance speech was similarly snipped when she referred to "my incredible wife Tammy." It was reduced to "my Tammy" by the republic's guardians of morality.

Clearly any favourable mention of homosexuality is a no-no. Yet, Fridae operates out of Singapore, does it not? So, how does the system work, again?

The first thing to understand about the censorship system here is that it isn't a crude system where editors have to submit drafts up to dour bureaucrats for yes/no answers. On the contrary, Singapore's system is quite sophisticated, but in that sophistication lies a chilling effect that is far greater than a crude system would ever have. At the same time, it is designed to invisibilise censorship, thus allowing the government to deny heavy-handedness and to present an acceptable face to the international community.

Two key principles need to be grasped in understanding the Singapore system: the use of a mass/fringe distinction, and the strategy of delegating the actual censorship work away from the government.

The mass/fringe distinction

Different standards apply to different platforms, depending on the social impact of each platform. Thus, television is the most strictly regulated medium since the belief is that visual images can be very emotive and the effect of broadcast immediate. Moreover, within television, a distinction is made between free-to-air broadcasting, which has the strictest standards, and cable television, which gets a little more freedom. Free-to-air, reaching many homes at the same time is said to have more impact than cable channels which tend to reach fewer homes which are generally wealthier - by the government's logic, better-educated and more discerning.

The same logic applies to print. Mass circulation newspapers are watched very carefully, while weekly or monthly magazines get more leeway. The Economist's or Time magazine's stories are rarely interfered with, but this is not to say that local dailies can do similar stories.

The cinema has very detailed censorship standards, but live theatre, which tends to have smaller, more elite audiences, even permit full nudity on stage. As for the Internet, it is virtually unrestricted.

This mass/fringe distinction allows the government to boast about media freedom in Singapore when it is useful to do so, especially to foreign audiences. When people criticise them for only permitting state-controlled newspapers to circulate, the government points to how foreign newsmagazines can be imported, conveniently ignoring the fact that foreign magazines never devote much space to Singapore news.

When others highlight how dull and subservient the television stations in Singapore are, the government points to how the Internet is largely free, ignoring the fact that it is precisely the question of relative reach that makes it important to free up broadcasting.

The result is that free expression is limited to the margins. There's enough there for the government to boast that Singapore is not a stalinist state, but at the same time, the truth that is too often brushed aside by its apologists is that the main arena is a highly regulated space.

Delegating censorship

Much more insidious is the way the system delegates censorship away from government bureaucrats to corporate officers. The people who do the frontline censorship are usually the editors of newspapers and producers of TV programs. Others include distributors of feature films and book retailers, who look over their shoulders each time they decide whether to import a film or a book.

In the case of editors and producers, they know their jobs are on the line if they make any wrong moves since the board of directors above them is largely appointed by the government. In turn, through the daily influence of editors and producers, the reporters themselves internalise the culture of never asking probing questions of ministers, and avoiding stories on "sensitive" social topics.

Much of what is permitted or not permitted is unwritten, but even when there are published rules, one can never be certain how these rules will be interpreted, an uncertainty that makes editors and producers play safe, generally preferring a more conservative reading of the rules than may actually be warranted.

Thus, in the case of the comments snipped from Cynthia Wade's acceptance speech, when Fridae asked the government about it, the reply, one week later, from Cecilia Yip, Senior Assistant Director, Broadcast Standards, Media Development Authority, was in effect, to deny responsibility for it. She said: "The Media Development Authority (MDA) does not pre-censor programmes that are aired on TV. Broadcasters are guided by the MDA's TV Programme Code, which outlines the general standards to be observed by broadcasters for television broadcast.... Broadcasters are free to edit programmes to suit their programme schedules."

Notice too the red herring - "to suit their programme schedules," diverting attention from MDA's censorship requirements.

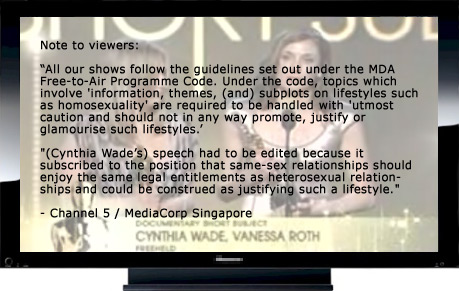

A few days later, the reply from the broadcaster, Mediacorp, came through. David Christie, a senior programme manager said in an email: "All our shows follow the guidelines set out under the MDA Free-to-Air Programme Code. Under the code, topics which involve 'information, themes, (and) subplots on lifestyles such as homosexuality' are required to be handled with 'utmost caution and should not in any way promote, justify or glamourise such lifestyles'.

"While documentary producer Cynthia Wade's comments indeed addresses the issue of discrimination, it specifically refers to discrimination of same-sex relationships. Her speech had to be edited because it subscribed to the position that same-sex relationships should enjoy the same legal entitlements as heterosexual relationships and could be construed as justifying such a lifestyle."

As you can see, the government said they didn't censor. Mediacorp said they had to censor because that's what the government wanted them to do. But you would also have noted, it's all a matter of interpretation too. You're being strangled by shadows.

Saying yes and no simultaneously

Another example of how uncertainty reigns supreme: In January this year, Mediacorp aired an episode of a reality TV show, where a married gay couple went about looking for secondhand items to spruce up their adopted son's room. Someone named Bennie Cheok then wrote to the press complaining that a gay family nucleus had been shown on TV. Nominated Member of Parliament Thio Li-Ann raised the matter again in early March.

The Senior Minister of State for Information, Communication and the Arts, Balaji Sadasivan, said in reply to Thio that the gay relationship was merely an "incidental feature" of the programme, and that Singaporeans would "need to take a balanced view".

While that may sound very hopeful, he also said TV would continue to promote traditional family values, and that Mediacorp was being investigated for the above-mentioned incident. So, they're not off the hook.

Which means what? Allowed or not allowed? You never know where you stand and this debilitating uncertainty eventually makes legions of corporate executives and ordinary citizens part of the conspiracy, censoring yourself, censoring others around you in case what they do gets you into trouble. Meanwhile the bureaucrats can claim they have not wielded the scissors at all.

That's the other side of Singapore's famed efficiency.

13 Mar 2008

the invisible scissors

Fridae first reported that part of director Cynthia Wade's speech made during the acceptance of her Oscar award was snipped when it was shown on Singapore TV... Alex Au attempts to decipher what's allowed and what's not based on replies by the broadcasting authority and broadcaster.

Singapore