Valentine’s Day 2010; China Daily’s picture of a lesbian couple from the Beijing Tongzhi Group dressed in wedding dresses on the streets of Beijing is flashed around the world, the headline ‘Gay Rights in China: ROAD TO RESPECT’. What is not shown is the film crew which had filmed the couple in Qianmen Street on the previous year’s Valentine’s Day or its director, Fan Popo. China Daily’s stills were taken during filming of Fan’s second gay Chinese film, New Beijing, New Marriage.

Fan Popo, 25, studied film research for four years at the prestigious

Beijing Film Academy before he found his calling as a filmmaker.

All photos courtesy of Fan Popo.

Aged only 25, Fan has already three films on LGBT subjects under his belt. These, plus the road show he and friends put together two years ago to bring LGBT film to China’s major cities, brought him an invitation to attend the Chinese University of Hong Kong’s week-long Gender and Sexuality Festival this March. Over a day, Fan showed the festival audiences six films in Putonghua (four of them documentaries, one a cartoon and one a "docudrama") and talked to them about the LGBT situation in China, concentrating particularly on cultural aspects. In between sessions, he came down to Central to meet me at the Foreign Correspondents Club to tell me about his work on film and on the road.

His career has had a meteoric trajectory. “My first ‘gay experience’ was when I was aged 3,” he told me. “I remember sitting on my mother’s lap watching TV and seeing a handsome guy. I was attracted to boys all the way through school; I had very strong emotions and told many of them I loved them!” He was usually rebuffed, but not always, and apart from being made continual fun of he wasn’t bullied for his honesty.

Home was in a country district of Jiangsu where no one understood homosexuality and few do now (though his parents do, as he has told them about it). Later, as a student, he was exposed to the more sophisticated ways of the capital, where he studied film research for four years at the prestigious Beijing Film Academy.

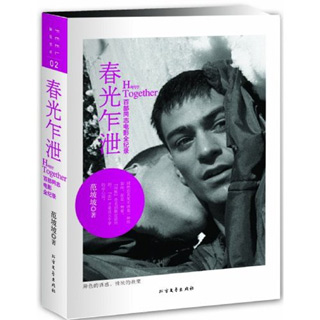

Whilst studying, Fan collected a very large number of queer movies, which he was always recommending to his classmates. He found that some of them who had been homophobic began to understand LGBT people through watching the films and this opened his eyes to the power of film, not, of course, to change people's sexuality, but to alter opinions about sexual minorities. Fan began to write papers about queer movies in his classes (one of them won an LGBT prize from the Chi Heng Foundation). There were then no books about queer film in mainland China, so when he had written a lot of articles on this topic, he collected them in a book and set out to find a publisher. He had great encouragement from Professor Cui Zi’en, the leading light in China’s LGBT film world, who had earlier been sacked from the Academy after he had come out as gay and now works as an independent film maker. With help from Cui, the book was published in Chinese in 2007, two months before Fan graduated. It is entitled Chunguang Zhaxie: Baibu Tongzhi Dianying Quanjilu, or Happy Together: 100 Queer Films All Included.

Whilst doing all this, Fan was also writing TV shows and by the end of his course had saved enough money to buy a digital video (DV) camera. After graduating, he tried his hand at writing screenplays (which he found dull), wrote newspaper pieces about film then turned to making films himself. With support from Aizhixing (the Beijing HIV NGO), Fan Popo went to Taiwan in 2007 to work with the Taipei LGBT Civil Rights Movement (which is the name for the annual LGBT festival there, rather than a movement), and showcased this in a short film called Taipei: City of Rainbow. This was shown at the fourth Beijing Queer Film Festival (of which Cui Zi’en was an organiser) in June 2009. Fan is a Committee Member of the Festival, too.

“The Central Government has total control over what is shown in cinemas,” Fan tells me, “and films with gay subjects are forbidden. The Beijing Queer Film Festival has been troubled by the police several times. So we wanted a safe way to show films and to speak out to the community.” So, with actress Shitou (a lesbian who starred in what was billed as China’s first mainstream lesbian film, Fish and Elephant, in 2001) and Bin Xu, (an LGBT activist in China since 1995 and Director of Common Language, a support and rights group for lesbian, bisexual women and transgender people in China), Fan founded China Queer Independent Films.

In February 2008, they launched the China Queer Film Festival Tour, which has already shown over seventy screenings of LGBT films in eighteen cities around China. “We show films in many different venues,” Fan adds, “gay and lesbian clubs, LGBT cultural centres, straight film salons and even universities. We used to have to beg for places to take our shows; now they are asking us to come. We hold talks after the films about LGBT subjects and try to educate our audiences, many of whom are heterosexual.”

Everything is self-funded, and the costs of the endless train and bus travel and the cheap accommodation are covered only in part by the minimal ticket charges (usually set at RMB 20/US$3, or RMB 30 a head). They sell books, DVDs and postcards and take local donations as they travel to make it all work. They’ve also had help from gay magazine Gay Spot and from Les Plus, the lesbian journal, as well as from the Beijing Queer Film Festival, the Beijing LGBT Centre and webcast Queer Comrades, all of which have shared resources to help make the tours possible. I ask Fan whether the Government had ever tried to stop their work. “No, not at all,” he answers. “We kept our project low profile at first but are more open now. We’ve been mentioned by China Daily and on the LGBT website aibai.com. When we’re on tour, a lot of people are very shy of having much to do with us at first,” he adds.

Actress Tilda Swinton in a “We want to watch homosexual movies!" tshirt

at the first Scottish Film Festival in China in March 2009.

“When we reach a tour destination, many will not walk with me, but after a few days they are asking to wear one of our t shirts,” one of which this reporter is very proud to possess and which states boldly in Chinese “We want to watch homosexual movies!” Tilda Swinton wore one at the first Scottish Film Festival in China in March 2009.

Chinese gay film makers often concentrate on coming out stories, and Fan is no exception. Whilst on tour, he interviewed many gay men and lesbians who had come out to their parents, putting their experiences together in his film The Chinese Closet, which was released in 2009. “Coming out is still a very big issue in China,” says Fan. “One day, it’ll be a forgotten thing, but now we need to educate closeted LGBT people and help them come out.”

Fan at the 'Only Love' club in Nanning, the capital of

Guangxi autonomous region in southern China.

His next film, Only Love, takes a different theme, this time looking at the experience of transgender people in Nanning, in the south of China. It’s under production now. You’ll be very lucky to see any of his films, regrettably, as they aren’t published outside China and as far as Fan is aware are not on the net yet. This was indeed one of the assumptions of many of the films’ participants, who were often prepared to be featured on films that would be shown to small and discreet audiences but did not give permission for their interviews to go on general release, where they might be spotted by people who knew them.

LGBT film making is still fraught with difficulty in China as cultural censorship works to keep LGBT subjects out of mainstream films and to prevent their showing in public cinemas. Gay film makers who want to make films about the gay experience can’t get funding, though there’s more chance of finance for a film about HIV and in a very few cases some foreign film foundations can be found to help out. This is not only an issue of party political doctrine or control, thinks Fan, more the traditional moral conservatism ensconced in the administration. Confucius and the primacy of the family have lost little of their power.

Despite his youth, Fan has suffered for the last six years from lumbar disc protrusion, a complaint that runs in his family, and which recently kept him in bed for a full two months. “I will not give up holding the camera”, he says, “it’s something I love. Even though my camera is very heavy, when I was ill in bed I had to hold it.” Symptomatic, I think, of the bravery with which he conceived and implemented his project.