I have nothing but respect for guerilla filmmakers. You know, people who shoot films on the sly without any permission or film permits. In an earlier recession, I tried that once with a group of newly graduated (and hence unemployed) classmates. A concerned citizen spotted us, called the police up and minutes later at around 4 am in Shenton Way, a police car approached our crew. The very nice boys in blue told us that there’s no law against filming on the sly in Singapore, but we do need a permit if we intended for our film to be commercially distributed. We shrugged, they shrugged, and they left us to continue our filming – much to the annoyance of Mr Concerned Citizen who was spying on our encounter from a distance.

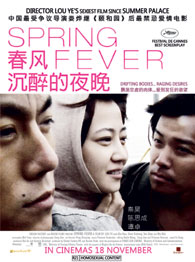

Lou Ye is a guerilla filmmaker par excellence. Unlike us, he was actually banned from making films when he made Spring Fever. I understand that since his film went into the world, the Chinese have extended that ban on him. How do you make a guerilla film? It’s easy and difficult at the same time – so as not to arouse attention, you employ very humble handheld prosumer equipment (no additional lights, no dollies, no tracks, no director’s chair!), film what is completely ordinary.

The look of your film, the angles and shots you employ will all be constrained by the fact that you were shooting all this on the sly. To anyone on the street, you were making an uninteresting film about an uninteresting subject, filmed in an uninteresting way – either extreme close ups or voyeuristic long shots. The story comes together only in post-production, where the ordinary is reconstituted, where the voice of the director is reinstated.

What does Lou Ye want to say to us via Spring Fever? It turns out it’s the same things his previous films are preoccupied with – a phenomenological account of everyday existence, the everyday lust for life (or lust itself) of everyday citizens, and ultimately the realisation of a futile, furtive existence. The players are a gay man, his accidental bisexual lover, and that lover’s girlfriend. The story is Jules et Jim with the love triangle and sexual politics inverted.

One gathers that years of state-imposed silence has made Lou Ye’s desire to speak more desperate. Truth be told, his cup runneth over in this film. Despite the slice of life format and the meandering twists and turns that are destined to lead nowhere (and wouldn’t work otherwise in this genre), we get the sense that Lou Ye wants to say so much on so many subjects and that it might not all fit into the same film.

The result is a film that feels out of place with itself. Moments of existential nihilism jostle uncomfortably with soap opera queer melodrama complete with characters screaming at each other. A laconic, just-so narrative that Camus would have flinched at is also host to impossibly overwrought and precious lyrical scenes where characters recite moody poetry to each other about the futility of existence or sing karaoke songs about the beauty of life.

At two hours, you gather that there’s 80 minutes of a good, well-focussed arthouse film in there – but Spring Fever is not much of a gay film and not so much an arthouse film as a guerilla film made by a guerilla filmmaker who has been silenced too long to constrain himself, even artistically.