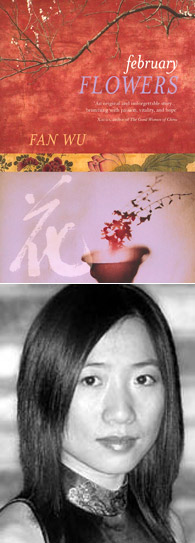

It sounds like a terrible teenage romance, but February Flowers is a hot new Chinese dyke book.

Fan Wu's debut novel February Flowers deals with the themes of sexuality and sexual repression during China's Cultural Revolution. Originally from China, she attended Sun Yat-Sen University in Guangzhou before being awarded a scholarship to do a Masters degree in communication at Stanford University in 1997. She now lives in California.

"It's about a strong bond between two very different university girls and how that kind of closeness can be daunting," is as far as Wu went in a recent interview in Beijing.

But from the opening chapter to the final paragraph, the novel, which is written in English, focuses heavily on 17-year-old Chen Ming's desire for her friend, Miao Yan, 24.

A desire that makes Chen's heart pound, a desire that strikes her with a dizziness that is a kind of ecstasy, a desire that makes her panic at Miao's touch, a desire that survives more than 12 years and travels from Guangzhou to San Francisco.

But "it's a coming of age story," insists Wu, echoing the blurb of her publisher, Picador Asia. "As well as a meditation on loss, love and forgiveness." The perplexing title comes from a Tang dynasty poem about the resilience of blooms surviving a harsh winter.

Thirty-three year old Wu is the latest in a line of celebrated Chinese authors after Ha Jin (Waiting) and Lu Yiyun (A Thousand Years of Good Prayers) who have penned their work in English.

The novel focuses on Chen and her first year at university in Guangzhou in the early nineties. Bookish and introverted, Chen struggles with her feelings, both emotional and sexual, for Miao, who is in every way her opposite - cocky, flirtatious and an academic slacker.

"In later years, whenever my friends talked to me about their first love, I would think of this moment when I saw Miao Yan dancing in the morning light," Chen says after the wayward Miao sneaks into her dorm at dawn to show off her new clothes.

Wu agrees that her book is likely to strike a chord in many an Asian lesbian's heart and that she was inspired to focus on homosexuality because some of her friends at the time were going through those experiences.

She says she borrowed from much of her own life to create Chen.

"I gave the younger character [Chen] a lot of my own experiences. In that way I could make it very authentic."

Like her novel's heroine, Wu grew up on a farm in southern China after her family was exiled there during the Cultural Revolution. She went on to study Chinese Language and Literature at Sun Yat-Sen University in Guangzhou and like Chen was a voracious reader.

"But I am a lot more rebellious than she is," she laughs.

How about Chen's passion for Miao?

Wu smiles and looks away coyly. "No, no," she says. "I didn't have such experiences. But some of my friends went through them."

One of the novel's strongest themes is the prevalence and extent of sexual ignorance among young adults in China at that time.

There's a scene in the book - which Wu says actually happened to her when she was 17 - where Chen and her two dorm mates - Donghua and Pingping -- discuss sex. Donghua thinks kissing can make a woman pregnant, while Chen knows that it's something to do with sleeping together but doesn't know what that means. Pingping shocks them both by explaining what happens during sex. She shows them their first porn magazine and Chen panics when she finds herself getting aroused by the photos.

When they come across a picture of two women kissing, Donghua announces: "Homosexuals? I've heard about them. They have a mental illness. They must be Americans. I heard there are a lot of them in the US."

The diminutive Wu, who even with her two-inch heels still hovers around five foot, becomes animated when she talks about sexual ignorance.

"When I was growing up in China there was no sex education at all," she says. Her words are clipped staccato short like many Chinese expatriates, but grounded with an American twang.

"When you are a teenager you don't dare to think about same sex love; you don't have the knowledge.

"I had no concept of homosexuality when I was growing up. I only heard about it in college."

And although things have improved for urban youth since her day, she adds, sex education in the countryside is still vastly inadequate.

It is this China, she says, that she wanted to write about. She is scornful of contemporary novelists who shock with stories of China's descent into a drugs and sex culture in books like Shanghai Baby and Beijing Doll.

"I hate it when people compare me with Wei Hui [author of Shanghai Baby]," she says forcefully.

"The book started people talking about a sexual liberation in China... But this is not true. Yes there is some rebellious element but this [these novels] are an exaggeration.

"I wanted to write about the real China - there are too many stereotypes and myths about real Chinese people."

Wu's book was rejected around 50 times by American publishers before it was picked up by a British company.

"I tried to find an agent in the US - but they said it was too Chinese; it was not explicit enough," she says.

"They wanted me to explain what exactly is going on between the two girls; they wanted to make it more like a memoir. But that's not for me."

Is Chen really gay?

Wu laughs, shakes her long, sleek hair and says, "Make your own mind up!

"This question was fiercely debated by my friends in the States. They demanded to know an answer," she says. "But being a reader is about filling in the gap yourself.

"It's not decided by me. The characters decide. And I'm not writing any sequel."

February Flowers (242 pages) is available online at www.selectbooks.com.sg (international shipping possible).

Printable Version

Printable Version

Reader's Comments

Please log in to use this feature.